For the past three and a half years I have been working for a start-up in downtown Vancouver. We have been developing a high performance SMTP proxy that can scale to handle tens of thousands of connections per second on each machine, even with pretty standard hardware.

For the past 18 months I’ve moved from working on the SMTP proxy to working on our other systems, all of which make use of the data we collect from each connection. It’s a fair amount of data and it can be up to 2Kb in size for each connection. Our servers receive approximately 1000 of these pieces of data per second, which is fairly sustained due to our global distribution of customers. If you compare that to Twitter’s peak of 3,283 tweets per second (maximum of 140 characters), you can see it’s not a small amount of data that we are dealing with here.

So what do we do with this data? We have a real-time global reputation network of IP addresses that send email. We use this is identify good and bad senders. The bad being spambots. We also pump this data into our custom-built distributed search engine, built using Apache Lucene, which is no small task when we aim to get search results live within 30 seconds of the connection taking place. This is close enough to real-time for our purposes.

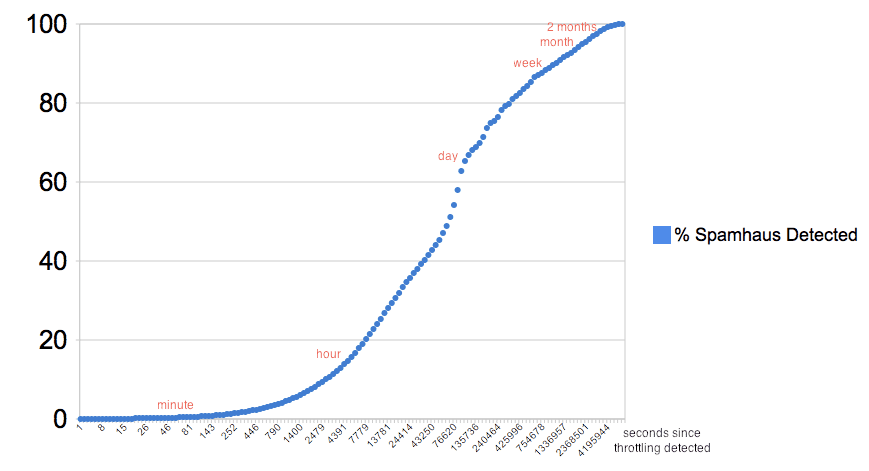

I recently set out to scientifically prove the benefits of throttling, which is our technology for slowing down connections in order to detect spambots, who are kind enough to disconnect quite quickly when they see a slow connection. Due to the nature of the data we had, I needed to work with a long range of data to show evidence that an IP that appeared on Spamhaus had previously been throttled and disconnected, and then measure the duration until it appeared on Spamhaus. I set a job to pre-process a selected set of customers data and arbitrarily decided 66 days would be a good amount to process, as this was 2 months plus a little breathing room. I knew from my experience it was possible that it might take 2 months for a bad IP to be picked up by Spamhaus.

I will not go into the details of the results here, as they can be found on the MailChannels blog post entitled Comparing Spamhaus with Proactive Connection Throttling, but the cool things about this was the amount of data that needed to be processed. I extracted 28,204,693 distinct IPs, some of which were seen over million times in this data set. Here the graph of the results I found. I thought the logarithmic graph looked perfect.

Graph taken from the MailChannels analysis of Spamhaus Vs Throttling

Have you worked with large amounts of data that does not get the same fanfare attention as the Twitter firehose by bloggers such as Mashable? I’d really like to hear your stories.

Very cool stuff. I’ve always been hesitant to blog about anti-spam for fear of spammers picking up on it and modifying their techniques. Are you concerned that spammers might do that in this case?

I’m just starting a tech company and hope to be dealing with large data sets. It’s a balance between planning for the future and acting now. If there’s no action now, there’s not future but without planning the future will be disastrous.

Well, if you have a technology that you intend to sell, then you need to talk about it, and the bad guys usually figure it out quickly enough anyway. Actually, I’ve recently moved on from MailChannels to start my own tech company, so I’m not trying to sell the technology right now. Without getting into too much detail, slowing connections targets the economics of sending spam. Spammers have to get an enormous amount of spam out to get enough people to click on the links or buy of the controversial pharmaceuticals that they are selling. Their click-through-rate is incredibly small. Even if they know you are slowing them down, they do not have the time to wait around. It’s better for them to move onto the next guy.

My approach to starting a tech company is getting things up and running as quickly as possible. Use the languages and tools that you are most comfortable with. You do not need to scale until you are successful, at which point it’s easier to rewrite things in a more scalable way, or hire somebody else who knows how to do it, and concentrate on putting out the other fires in your successful business. You’ll probably be rewriting things anyway as the product or service evolves and you learn more about the need that you are addressing. When you make things scalable you lock yourself into certain choices that limits your ability to be dynamic.

@Phil excellent post. I appreciate the problems you face when dealing with extremely high numbers in a short space of time. Your distributed search with Lucene sounds interesting. Would love to hear more about that in future.

One method we use with extreme effectiveness is the use of the data structure, BloomFilter. This data structure is an extremely effective tool for determining if you have seen something before without any expensive database or search lookup. It is the technology a lot of the big hash map implementations use internally.

Hi Alan,

Thank you for the comment. The Bloom Filter does sound like a great tool, that I’ve not come across before. I will have to read up on it.

In this case, where the goal is to build concrete statistics, I think the false-positive aspect of the Bloom Filter would have affected the results. Even if it was ever so slightly, I would have felt uncomfortable publishing them and referring to somebody else’s technology (Spamhaus in this case) where I knew there may be a slight inaccuracy.

I see that the Bloom Filter addresses memory consumption. Since I had so much data, memory was not an issue. That’s sounds backwards and it is. Since the data cannot possibly fit into a machine memory, I used several technics I discovered from working with Hadoop. Basically streaming data to and from disk in the most efficient way, performing several transformations of the data and writing the data to disk to divide, organise, sort, merge and conquer. I think the peak memory I used was far less than I had on the machine, and this was generally highest when sorting the individual files.

I’m considering writing a blog post on the details of how I tackled this data, as this blog post proved to be quite popular. Would that be something you would be interested in?

If you want to see bloom filters used in spam processing, you could check out gross[1] that uses them for greylisting. It has proven[2] itself quite efficient way to block large amount of spam.

[1] https://code.google.com/p/gross/

[2] https://lists.utu.fi/pipermail/gross/2007/000035.html

Hi Antti,

My experience, from working with our customers at MailChannels, was that grey-listing started to become ineffective a couple of years ago as the spambot writers started to incorporate this technology into their software and perform retries, just as a legitimate email server would. Not actually having worked with grey-listing myself, I do have any hard figures to back-up conversations with customers, who sometimes became our customers whilst looking for alternatives to grey-listing.

You are obviously an expert in this area, so I would be really interested in any statistics or other data you have on the effectiveness of grey-listing. Do you have a blog?

Thanks,

Phil

Thats awesome, congratulations. It’s really refreshing to see these kinds of innovations coming out of Canada, even it if it Vancouver and not Toronto lol =)

Thanks Michael. Hopefully Toronto will catch up with the technological juggernaut that Vancouver is.

On a serious note, MailChannels is developing some very cool stuff in the anti-spam space. They’re expanding the development team right now, so if there is anyone in Vancouver interested, you should pop in and say hi.

You might want to look at s4 by Yahoo. They recently open-sourced it.

Thanks Montreal Web Design. Here’s a link for anyone interested https://s4.io/